The 21 May flare was one of the most intensively studied at that time. It was a big (X-class) flare, it did lots of different, interesting things and was inspected by several leading edge instruments, like HXIS. So many people wrote articles on aspects of this flare that it eventually played the starring role in its very own review article, where two famous solar astronomers summarised the various studies and drew them all together.

Many individual solar flares have been important in our developing understanding of these events: the first big flare seen in some new instrument, a flare that did something in a particularly simple way so that cause and effect seem clearer than in most cases, a flare that did something dramatic never seen before.

Over the decades there have been many such significant events. This was useful when I was young and frivolous. Today, for example, we could say, "it's the anniversary of the 21 May 1980 flare. We need to celebrate this - let's go to the pub!" In fact, if we scoured the solar physics literature we could probably find a solar flare to celebrate on most days of the calendar, especially now a couple of decades on: 13 January, 20 January, 23 February, 24 May, 3 June, 7 June, 14 July, 28 October....that's enough, you get the point, and I'm sorry so few of them have nice web resources and so many of the links are technical. Maybe that should be a wee job for somebody: "Flare of the day" blog. Anyway we never needed to wait very long to have an excuse for a wee pub visit, and if we really needed an excuse we could probably scour the literature and find somebody with their own wee solar observatory, lost and forgotten in the woods or clinging to some unvisited mountainside in some far-off and exotic land, who had observed a flare on that particular date.

Anyway, nowadays those pub visits are much rarer. We probably only used a famous solar flare as an excuse on a few occasions, to be honest - most of the time we didn't worry about excuses. But as I headed home on the bus this beautiful May day, I spotted lots of people sitting outside enjoying a beer or a glass of wine and I was glad to see that the X-class footpoint flare of 21 May 1980 is still celebrated vigorously.

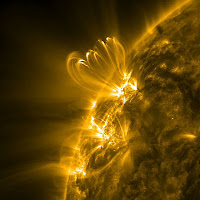

Image: NASA Solar Dynamics Observatory AIA instrument ultraviolet image of solar loops from January 2012