Let's start in familiar territory. In A Brief History of Time, Stephen Hawking dragged God into the popularisation of Physics. In what was probably only ever meant to be a throwaway comment he suggested that success with a unified theory of the fundamental forces and particles would be equivalent to "knowing the mind of God". The G-word was invoked by more than one of the scientists involved in the

COBE experiment. COBE measured the fluctuations in the cosmic microwave background radiation, the

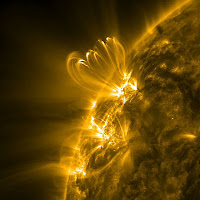

ripples in the early universe that eventually developed into the clusters of galaxies we see today; no stars, no planets, no us without those ripples. One of its Principal Investigators, George Smoot was (probably mis-)quoted: this discovery was "like seeing the face of God".

What would the face of God look like? (Atheists, please don't stop reading) I'm not convinced that sight of it would be pleasant.

You've lived for a few months in a huge, ancient, rambling house bought with the substantial wealth your mysteriously absent father somehow accumulates. You don't go to school. In the mornings, impatiently but with some flair, your mother teaches you mathematics, philosophy, history, some sciences, a couple of foreign languages, all of which you gobble up effortlessly, unaware you're years ahead of your contemporaries in attainment. In the afternoons Mum drinks sweet wine and watches DVD's of Doris Day movies. You're left to roam the house, to speculate on the functions of the peculiarly shaped furniture left in the upstairs rooms and the significance of the sombre grotesques painted on the wood panels of the less well-lit corridors.

One day at the end of an upstairs corridor you open a door you've ignored until now. You're surprised to find a previously unsuspected staircase, steep, narrow, uncarpeted, leading to a previously unknown part of the house. At the bottom of the stairs a few doors open off a corridor, empty, musky rooms with little interest. Under the stairs there is a small cupboard door which you open. After some moments peering into darkness you're astonished to see two large eyes looking back at you, solemn and expressionless. As you stare the face gets easier to see and you realise that it is shining more and more brightly itself. Your eyes start to hurt and you're aware of awful danger but it's too late. Brilliant mind is unprepared and body inadequate to deal with what happens next. The last episode of intolerable pain combines with an impression of incandescent beauty and you're grateful for the sense of transcendence that fills your last moments.

Last night I saw the American band Swans play live at the Arches here in Glasgow. Swans' fearsome reputation is nicely summarised in this review of a gig in Boston a couple of months ago. I was vaguely aware of their music but didn't know it well and had never seen them live before. As friends know I enjoy music that pushes at the edges in some way, technically, sonically, just emotionally. Although slightly wary, particularly of the stories of extreme volume, I thought I'd give Swans a go.

The opening number started slowly and quietly, with a sort of slow, psychedelic music. This is OK, like space rock but better, I thought; and of course the lyrics were more interesting, straight to some existential statement. "There are millions and millions of stars in your eyes," sang Michael Gira, a couple of times. His arms were outstreched in messianic style. I knew some upsurge was imminent but I was still shocked by the huge blast of sound that erupted, a furiously strummed chord, crashing drums, sustained without change for maybe a minute. My trousers flapped, maybe also my jacket. For a moment I thought I might throw up. The noise stopped, the space rock sounds resumed briefly and then the noise started for another minute or so; tens of seconds at least. This pattern repeated five or six times and the song came to an end. It struck me that these enormous blasts of noise were not just kids making a racket - these guys are my age and they've been doing it for decades - but a very deliberate reaching for a transcendent state through sheer volume and a sort of heavy metal minimalist repetition: what would it feel like with "millions and millions of stars in your eyes"?

(I shouldn't even mention heavy metal. Entertainment for kids. Cartoon music compared to this.)

Just a few songs kept this incredible, overwhelming racket going for a couple of hours. Early on I felt I might just leave but I resisted that urge; the point was to take the noise, to learn from it. I didn't feel physically sick again after the first song. I did wonder more than once if the bones of my ribcage might be shaken loose. Once I put my finger in my ear to see if there was blood (there wasn't).

Most of the intense music I enjoy reaches for transcendence by very technical means, playing fast, loud certainly, achromatic, building tension with odd time signatures and additive rhythms, exploring the extended possibilities of the instruments; free jazz starting from John Coltrane and Ornette Coleman for instance, or the "avant" end of progressive rock. Swans' music is not hugely technical. It struck me that this is deliberate, part of its mechanism. It would be wrong to put guitar solos in this music, or polyrhythms or cleverness, it would rob it of its sheer weight. It would be dishonest. Nonetheless there is a subtlety and art in it, because they are able to increase tension slowly, over say ten minutes, from a state already almost overwhelming in its intensity.

Towards the end of the gig I'd stopped thinking, waiting for something different to happen. I simply felt the sound and its changes from one moment to the next, lived in the middle of it. I was a recalcitrant child brought to heel, led to the correct behaviour by insistent repetition. I understood the look of ecstacy on Michael Gira's face.

It struck me that the Arches had become an extreme place, somewhere with a strange and terrible beauty, with amazing rewards for those with the stomach to tolerate it but a place that many would choose to avoid; maybe back to Herzog territory. Pals know that I've enjoyed a lot of gigs that would make most peoples' hair stand on end but this was still a stand-out of extreme intensity. Did I enjoy that gig? I'm still not sure. I'm also not sure if I would go to see them again but I'm glad I've been once.

"Spirituality" and "transcendence" are words often used in connection with Swans' music. I think that fearsome, repetitive noise aims to look on the face of God (although they might not say it that way). I also think these transcendent experiences enrich life whether or not you consider yourself religious. Many of my fellow scientists have had interesting, thoughtful things to say on religion (a wee example). Before they drag God casually into science popularisation, however, I think they should experience Swans live.